The radial-arm water maze is a common test to assess working memory in rodents.

Memory-enhancing drug reverses effects of traumatic brain injury in mice

By Ryan Cross, Jul. 10, 2017, sciencemag.org

Whether caused by a car accident that slams your head into the dashboard or repeated blows to your cranium from high-contact sports, traumatic brain injury can be permanent. There are no drugs to reverse the cognitive decline and memory loss, and any surgical interventions must be carried out within hours to be effective, according to the current medical wisdom. But a compound previously used to enhance memory in mice may offer hope: Rodents who took it up to a month after a concussion had memory capabilities similar to those that had never been injured.

The study “offers a glimmer of hope for our traumatic brain injury patients,” says Cesario Borlongan, a neuroscientist who studies brain aging and repair at the University of South Florida in Tampa. Borlongan, who reviewed the new paper, notes that its findings are especially important in the clinic, where most rehabilitation focuses on improving motor—not cognitive—function.

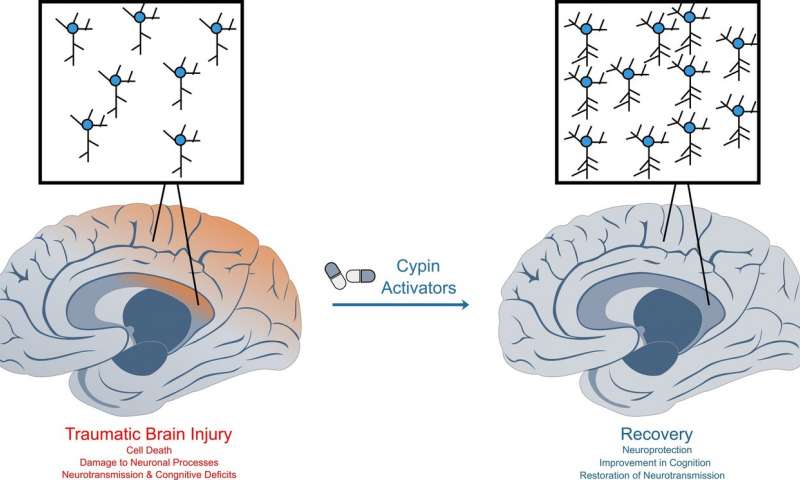

Traumatic brain injuries, which cause cell death and inflammation in the brain, affect 2 million Americans each year. But the condition is difficult to study, in part because every fall, concussion, or blow to the head is different. Some result in bleeding and swelling, which must be treated immediately by drilling into the skull to relieve pressure. But under the microscope, even less severe cases appear to trigger an “integrated stress response,” which throws protein synthesis in neurons out of whack and may make long-term memory formation difficult.

In 2013, the lab of Peter Walter, a biochemist at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), discovered a compound—called ISRIB—that blocked the stress response in human cells in a dish. Surprisingly, when tested in healthy mice, ISRIB boosted their memory. Wondering whether the drug could also reverse memory impairment, Walter teamed up with UCSF neuroscientist Susanna Rosi to study mouse models of traumatic brain injury. First, they showed that the stress response remains active in the hippocampus, a brain region important for learning and memory, for at least 28 days in injured mice. And they wondered whether administering ISRIB would help.

Rosi and her team first used mechanical pistons to hit anesthetized mice in precise parts of their surgically exposed brains, resulting in contusive injuries, focused blows that can also result from car accidents or being hit with a heavy object. After 4 weeks of rest, Rosi trained the mice to swim through a water maze, where they used cues to remember the location of a hidden resting platform. Healthy mice got better with practice, but the injured ones didn’t improve. However, when the injured mice were given ISRIB 3 days in a row, they were able to solve the maze just as quickly as healthy mice up to a week later, the researchers report today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We kept replicating experiments, thinking maybe something went wrong,” Rosi says. So the team decided to study ISRIB in a second model of traumatic brain injury known as a closed head injury, which resembles a concussion from a fall. They again used a mechanical piston, but this time landed a broad blow to the back of the skull. Two weeks later, the mice were trained on a tougher maze, full of bright lights and loud noise. They had to scurry around a tabletop with 40 holes, looking for the one with an escape hatch. Again, while the uninjured mice improved at the task, the concussed mice never got the hang of it. But after four daily doses of ISRIB, the concussed mice performed as well as their healthy counterparts. “This is the most exciting piece of work I’ve ever done, no doubt,” Rosi says.

“Paradigm shift is not too strong a term to use,” says Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, neurologist and director of clinical traumatic brain injury research at the University of Pennsylvania. “This … shows for the first time that a therapy in the chronic period of traumatic brain injury can have pretty potent effects.” Walter agrees. “Normally you would give up on these mice and say nothing can be done here,” he says. “But ISRIB just magically brings the cognitive ability back.”

Still, Borlongan cautions that studies in animals often don’t pan out when tested in humans. He says that this drug has a leg up, though, because it was tested in two models and also readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, which prevents many drugs that look good on paper from entering the brain and having an effect.

If the therapy translates to humans, it could be a boon for soldiers returning from war, who sometimes wait weeks between leaving the battlefield and arriving home for treatment. Brian Head, a neurobiologist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System in California notes that traumatic brain injury is still hard to diagnose, especially with veterans that show up to the clinic long after the injury. “But right now nothing else is working, and giving a compound [that works] a month later is really impressive.”

In 2015, ISRIB was licensed to the secretive Google spinout company Calico, which studies the biology of aging and life span. Walter says his lab has a research agreement with Calico to pursue “basic mechanistic work” on ISRIB, but that the new study was not funded by Calico. Google declined to comment on the new research.

Although the protein target of ISRIB is known, the exact manner in which the drug restores memory is hazy. The team hypothesizes that ISRIB may work by allowing normal protein synthesis—essential for making new neuronal connections and thus forming new memories—to resume, which would otherwise be blunted by the integrated stress response. “Even if this drug doesn’t materialize, other ways of manipulating the integrated stress response may lead to an effective treatment in the future,” Walter says.

Read the original article