Drug Reverses Age-Related Mental Decline Within Days, Suggesting Lost Cognitive Ability is Not Permanent

By Good News Network, December 27, 2020

Just a few doses of an experimental drug that reboots protein production in cells can reverse age-related declines in memory and mental flexibility in mice, according to a new study by UC San Francisco scientists.

The drug, called ISRIB, has already been shown in laboratory studies to restore memory function months after traumatic brain injury (TBI), reverse cognitive impairments in Down Syndrome, prevent noise-related hearing loss, fight certain types of prostate cancer, and even enhance cognition in healthy animals.

In the new study, published Dec. 1 in the open-access journal eLife, researchers showed rapid restoration of youthful cognitive abilities in aged mice, accompanied by a rejuvenation of brain and immune cells that could help explain improvements in brain function—and with no side effects observed.

“ISRIB’s extremely rapid effects show for the first time that a significant component of age-related cognitive losses may be caused by a kind of reversible physiological “blockage” rather than more permanent degradation,” said Susanna Rosi, PhD, Lewis and Ruth Cozen Chair II and professor in the departments of Neurological Surgery and of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science.

“The data suggest that the aged brain has not permanently lost essential cognitive capacities, as was commonly assumed, but rather that these cognitive resources are still there but have been somehow blocked, trapped by a vicious cycle of cellular stress,” added Peter Walter, PhD, a professor in the UCSF Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “Our work with ISRIB demonstrates a way to break that cycle and restore cognitive abilities that had become walled off over time.”

Rebooting cellular protein production holds key to aging

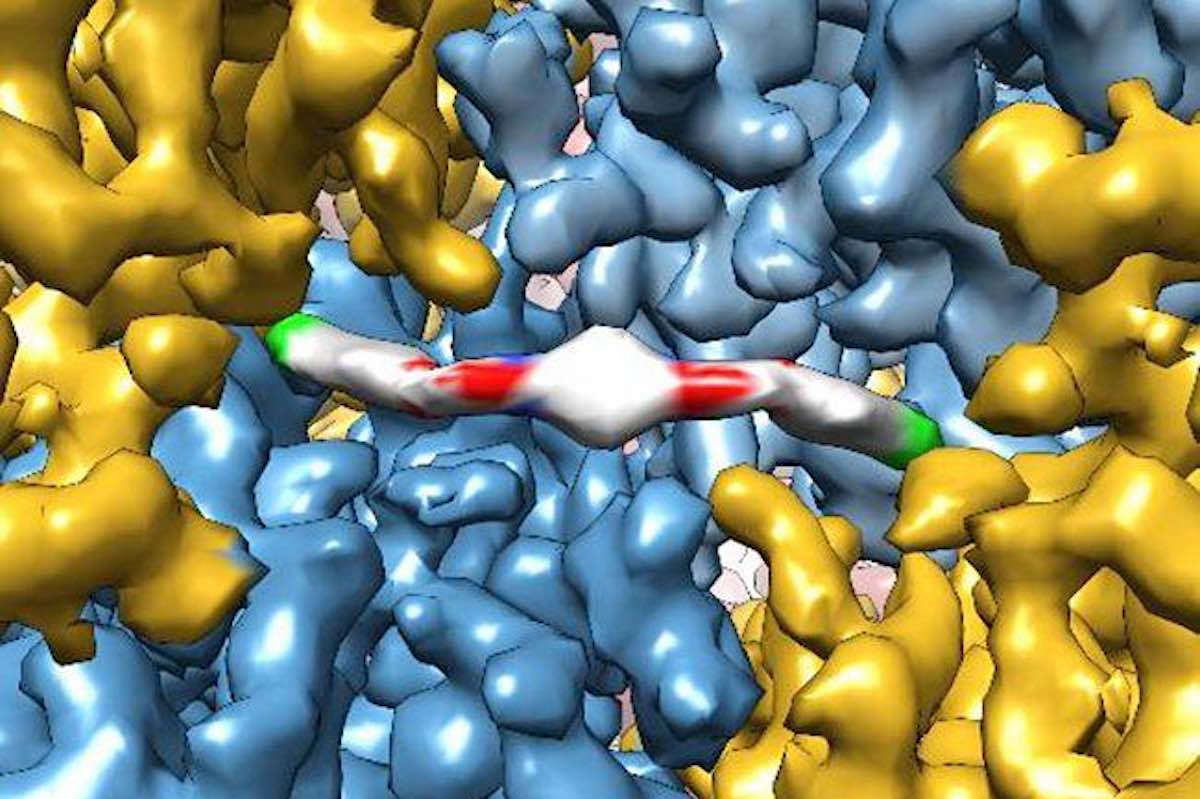

Walter has won numerous scientific awards, including the Breakthrough, Lasker and Shaw prizes, for his decades-long studies of cellular stress responses. ISRIB, discovered in 2013 in Walter’s lab, works by rebooting cells’ protein production machinery after it gets throttled by one of these stress responses—a cellular quality control mechanism called the integrated stress response (ISR; ISRIB stands for ISR InhiBitor).

The ISR normally detects problems with protein production in a cell—a potential sign of viral infection or cancer-promoting gene mutations—and responds by putting the brakes on cell’s protein-synthesis machinery. This safety mechanism is critical for weeding out misbehaving cells, but if stuck in the ‘on’ position in a tissue like the brain, it can lead to serious problems, as cells lose the ability to perform their normal activities, according to Walter and colleagues.

In particular, their recent animal studies have implicated chronic ISR activation in the persistent cognitive and behavioral deficits seen in patients after TBI, by showing that, in mice, brief ISRIB treatment can reboot the ISR and restore normal brain function almost overnight.

The cognitive deficits in TBI patients are often likened to premature aging, which led Rosi and Walter to wonder if the ISR could also underlie purely age-related cognitive decline. Aging is well known to compromise cellular protein production across the body, as life’s many insults pile up and stressors like chronic inflammation wear away at cells, potentially leading to widespread activation of the ISR.

“We’ve seen how ISRIB restores cognition in animals with traumatic brain injury, which in many ways is like a sped-up version of age-related cognitive decline,” said Rosi, who is director of neurocognitive research in the UCSF Brain and Spinal Injury Center and a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. “It may seem like a crazy idea, but asking whether the drug could reverse symptoms of aging itself was just a logical next step.”

Signature effects of aging disappeared literally overnight

In the new study, researchers led by Rosi lab postdoc Karen Krukowski, PhD, trained aged animals to escape from a watery maze by finding a hidden platform, a task that is typically hard for older animals to learn. But animals who received small daily doses of ISRIB during the three-day training process were able to accomplish the task as well as youthful mice—and much better than animals of the same age who didn’t receive the drug.

The researchers then tested how long this cognitive rejuvenation lasted and whether it could generalize to other cognitive skills. Several weeks after the initial ISRIB treatment, they trained the same mice to find their way out of a maze whose exit changed daily—a test of mental flexibility for aged mice who, like humans, tend to get increasingly stuck in their ways. The mice who had received brief ISRIB treatment three weeks before still performed at youthful levels, while untreated mice continued to struggle.

To understand how ISRIB might be improving brain function, the researchers studied the activity and anatomy of cells in the hippocampus, a brain region with a key role in learning and memory, just one day after giving animals a single dose of ISRIB. They found that common signatures of neuronal aging disappeared literally overnight: neurons’ electrical activity became more sprightly and responsive to stimulation, and cells showed more robust connectivity with cells around them while also showing an ability to form stable connections with one another usually only seen in younger mice.

The researchers are continuing to study exactly how the ISR disrupts cognition in aging and other conditions and to understand how long ISRIB’s cognitive benefits may last. Among other puzzles raised by the new findings is the discovery that ISRIB also alters the function of the immune system’s T cells, which also are prone to age-related dysfunction. The findings suggest another path by which the drug could be improving cognition in aged animals, and could have implications for diseases from Alzheimer’s to diabetes that have been linked to heightened inflammation caused by an aging immune system.

“This was very exciting to me because we know that aging has a profound and persistent effect on T cells and that these changes can affect brain function in the hippocampus,” said Rosi. “At the moment, this is just an interesting observation, but it gives us a very exciting set of biological puzzles to solve.”

Success shows the ‘serendipity’ of basic research

Rosi and Walter were introduced by neuroscientist Regis Kelly, PhD, executive director of the University of California’s QB3 biotech innovation hub, following Walter’s 2013 study showing that the drug seemed to instantly enhance cognitive abilities in healthy mice. To Rosi, the results from that study implied some walled-off cognitive potential in the brain that the molecule was somehow unlocking, and she wondered if this extra cognitive boost might benefit patients with neurological damage from traumatic brain injury.

The labs joined forces to study the question in mice, and were astounded by what they found. ISRIB didn’t just make up for some of the cognitive deficits in mice with traumatic brain injury—it erased them. “This had never been seen before,” Rosi said. “The mantra in the field was that brain damage is permanent—irreversible. How could a single treatment with a small molecule make them disappear overnight?”

Further studies demonstrated that neurons throughout the brains of animals with traumatic brain injury are thoroughly jammed up by the ISR. Using ISRIB to release those brakes lets brain cells immediately get back to their normal business. More recently, studies in animals with very mild repetitive brain injury—akin to pro athletes who experience many mild concussions over many years—showed that ISRIB could reverse increased risk-taking behavior associated with damage to self-control circuits in the frontal cortex.

“It’s not often that you find a drug candidate that shows so much potential and promise,” Walter says, calling it “just amazing”.

No side effects

One might think that interfering with the ISR, a critical cellular safety mechanism, would be sure to have serious side effects, but so far in all their studies, the researchers have observed none. This is likely due to two factors. First, it takes just a few doses of ISRIB to reset unhealthy, chronic ISR activation back to a healthier state. Second, ISRIB has virtually no effect when applied to cells actively employing the ISR in its most powerful form—against an aggressive viral infection, for example.

ISRIB has been licensed by Calico, a South San Francisco, Calif. company exploring the biology of aging, and the idea of targeting the ISR to treat disease has been picked up by many other pharmaceutical companies, Walter says.

“It almost seems too good to be true, but with ISRIB we seem to have hit a sweet spot for manipulating the ISR with an ideal therapeutic window,” Walter said.

Get more links to background studies from original article from UCSF News.

CLICK HERE to read the original article