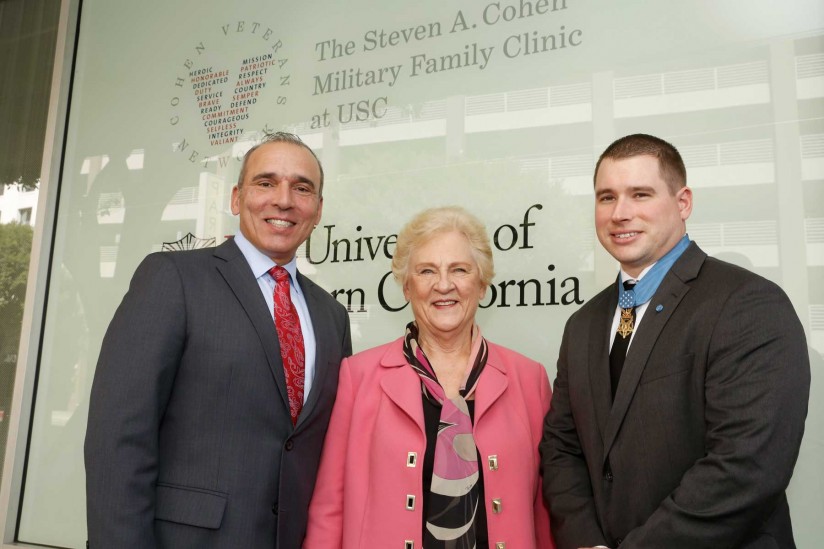

Libby and Tom Bates // CBS News

A brain disease best known for impacting football players who suffered concussions is now being found in soldiers

By Sharyn Alfonsi, September 16, 2018, CBS News

Until a few years ago, NFL players who struggled with severe depression, bouts of rage and memory loss in their retirement were often told they were just having a hard time adjusting to life away from the game. Doctors have since learned these changes can be symptoms of the degenerative brain disease CTE – chronic traumatic encephalopathy, caused by blows to the head.

As we first reported in January, CTE isn’t just affecting athletes, but also showing up in our nation’s heroes. Since 9/11 over 300,000 soldiers have returned home with brain injuries. Researchers fear the impact of CTE could cripple a generation of warriors.

When Joy Kieffer buried her 34-year old son this past summer, it was the end of a long goodbye.

Kieffer’s son, Sgt. Kevin Ash, enlisted in the Army Reserves at the age of 18. Over three deployments, he was exposed to 12 combat blasts, many of them roadside bombs. He returned home in 2012 a different man.

Joy Kieffer: His whole personality had changed. I thought it was exposure to all of the things that he had seen, and he had just become harder. You know, but he was — he was not happy.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So at this point, you’re thinking this decline, this change in my child is just that he’s been in war and he’s seen too much.

Joy Kieffer: Right.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Did he tell you about blasts that he experienced during that time?

Joy Kieffer: Uh-huh.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What did he–tell you?

Joy Kieffer: That they shook him. And he was having blackouts. And — it frightened him.

Ash withdrew from family and friends. He was angry. Depressed. Doctors prescribed therapy and medication, but his health began to decline quickly. By his 34th birthday, Sgt. Kevin Ash was unable to speak, walk or eat on his own.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Looking back on it now, was there anything you feel like he could’ve done?

Joy Kieffer: Uh-uh.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Because?

Joy Kieffer: Because it was– it– it was his brain. The thing I didn’t know was that his brain was continuing to die. I mean, before he went into the service he said, “you know, I could come back with no legs, or no arms, or even blind, or I could be shot, I could die,” but nobody ever said that he could lose his mind one day at a time.

His final wish was to serve his country one last time by donating his brain to science — a gesture he thought would bring better understanding to the invisible wounds of war.

Joy reached out to the VA-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation Brain Bank where neuropathologist Dr. Ann McKee is leading the charge in researching head trauma and the degenerative brain disease CTE.

McKee has spent fourteen years looking at the postmortem brains of hundreds of athletes who suffered concussions while playing their sport.

Last summer, her findings shook the football world when she discovered CTE in the brains of 110 out of 111 deceased NFL players — raising serious concerns for those in the game today.

And when Dr. McKee autopsied Patriots tight-end Aaron Hernandez who killed himself after being convicted of murder, she found the most severe case of CTE ever, in someone under 30.

Now she’s seeing similar patterns in deceased veterans who experienced a different kind of head trauma — combat blasts. Of the 125 veterans’ brains Dr. Mckee’s examined, 74 had CTE.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I can understand a football player who keeps, you know, hitting his head, and having impact and concussions. But how is it that a combat veteran, who maybe just experienced a blast, has the same type of injury?

Dr. Ann McKee: This blast injury causes a tremendous sort of– ricochet or– or– a whiplash injury to the brain inside the skull and that’s what gives rise to the same changes that we see in football players, as in military veterans.

Blast trauma was first recognized back in World War I. Known as ‘shell shock,’ poorly protected soldiers often died immediately or went on to suffer physical and psychological symptoms. Today, sophisticated armor allows more soldiers to walk away from an explosion but exposure can still damage the brain — an injury that can worsen over time.

Dr. Ann McKee: It’s not a new injury. But what’s been really stumping us, I think, as– as physicians is it’s not easily detectable, right? It’s– you’ve got a lot of psychiatric symptoms– and you can’t see it very well on images of the brain and so it didn’t occur to us. And I think that’s been the gap, really, that this has been what everyone calls an invisible injury.

Dr. Ann McKee: This is the world’s largest CTE brain bank.

The only foolproof way to diagnose CTE is by testing a post-mortem brain.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So these are full of hundreds of brains…

Dr. Ann McKee: Hundreds of brains, thousands really…

Researchers carefully dissect sections of the brain where they look for changes in the folds of the frontal lobes – an area responsible for memory, judgement, emotions, impulse control and personality.

Dr. Ann McKee: Do you see there’s a tiny little hole there? That is an abnormality. And it’s a clear abnormality.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And what would that affect?

Dr. Ann McKee: Well, it’s part of the memory circuit. You can see that clear hole there that shouldn’t be there. It’s connecting the important memory regions of the brain with other regions. So that is a sign of CTE.

Thin slivers of the affected areas are then stained and viewed microscopically. It’s in these final stages where a diagnosis becomes clear as in the case of Sgt. Kevin Ash.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So this is Sergeant Ash’s brain?

Dr. Ann McKee: Right. This is– four sections of his brain. And what you can see is– these lesions. The, and those lesions are CTE And they’re in very characteristic parts of the brain. They’re at the bottom of the crevice. That’s a unique feature of CTE.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And in a healthy brain, you wouldn’t see any of those kind of brown spots?

Dr. Ann McKee: No, no, it would be completely clear. And then when you look microscopically, you can see that the tau, which is staining brown and is inside nerve cells is surrounding these little vessels.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And explain, what is the tau?

Dr. Ann McKee: So tau is a protein that’s normally in the nerve cell. It helps with structure and after trauma, it starts clumping up as a toxin inside the nerve cell. And over time, and even years, gradually that nerve cell dies.

Dr. Lee Goldstein has been building on Dr. McKee’s work with testing on mice.

Inside his Boston University lab, Dr. Goldstein built a 27-foot blast tube where a mouse – and in this demonstration, a model – is exposed to an explosion equivalent to the IEDs used in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Dr. Lee Goldstein: When it reaches about 25 this thing is going to go.

Dr. Goldstein’s model shows what’s going on inside the brain during a blast. The brightly colored waves illustrate stress on the soft tissues of the brain as it ricochets back and forth within the skull.

Dr. Lee Goldstein: What we see after these blast exposures, the animals actually look fine. Which is shocking to us. So they come out of what is a near lethal blast exposure, just like our military service men and women do. And they appear to be fine. But what we know is that that brain is not the same after that exposure as it was microseconds before. And if there is a subsequent exposure, that change will be accelerated. And ultimately, this triggers a neurodegenerative disease. And, in fact, we can see that really after even one of these exposures.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The Department of Defense estimates hundreds of thousands of soldiers have experienced a blast like this. What does that tell you?

Dr. Lee Goldstein: This is a disease and a problem that we’re going to be dealing with for decades. And it’s a huge public health problem. It’s a huge problem for the Veterans Administration. It’s a huge moral responsibility for all of us.

A responsibility owed to soldiers like 34-year-old Sgt. Tom Bates.

Sgt. Tom Bates: We were struck with a large IED. It was a total devastation strike.

Bates miraculously walked away from a mangled humvee — one of four IED blasts he survived during deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you remember feeling the impact in your body?

Sgt. Tom Bates: Yes. Yeah.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What does that feel like?

Sgt. Tom Bates: Just basically like getting hit by a train.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And you were put back on the frontlines.

Sgt. Tom Bates: Yes.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And that was it?

Sgt. Tom Bates: Uh-huh

When Bates returned home in 2009, his wife Libby immediately saw a dramatic change.

Libby Bates: I thought, “Something is not absolutely right here. Something’s going on. For him to just lay there and to sob and be so sad. You know, what do you do for that? How do I– how do I help him? He would look at me and say, “If it wasn’t for you, I would end it all right now.” You know, I mean, like, what do you– what do you do– and what do you say to somebody who says that? You know I love this man so much. And —

Sharyn Alfonsi: You’re going to the VA, you’re getting help, but did you feel like you weren’t getting answers?

Sgt. Tom Bates: Yes.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And so you took it into your own hands and started researching?

Sgt. Tom Bates: I knew the way everything had gone and how quick a lot of my neurological issues had progressed that something was wrong. And I just– I wanted answers for it.

That led him to New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital where neurologist Dr. Sam Gandy is trying to move beyond diagnosing CTE only in the dead by using scans that test for the disease in the living.

Dr. Sam Gandy: By having this during life, this now gives us for the first time the possibility of estimating the true prevalence of the disease. It’s important to estimate prevalence so that people can have some sense of what the risk is.

In the past year, 50 veterans and athletes have been tested for the disease here. Tom Bates asked to be a part of it.

That radioactive tracer – known as t807 – clings to those dead clusters of protein known as tau, which are typical markers of the disease.

Through the course of a 20 minute PET scan, high resolution images are taken of the brain and then combined with MRI results to get a 360 degree picture of whether there are potential signs of CTE.

Scan results confirmed what Tom and Libby had long suspected.

On the right, we see a normal brain scan with no signs of CTE next to Tom’s brain where tau deposits, possible markers of CTE, are bright orange.

Dr. Sam Gandy: Here these could be responsible for some of the anxiety and depression he’s suffered and we’re concerned it will progress.

Sgt. Tom Bates: My hope is that this study becomes more prominent, and gets to more veterans, and stuff like that so we can actually get, like, a reflection of what population might actually have this.

There is no cure for CTE.

Dr. Gandy hopes his trial will lead to drug therapies so he can offer some relief to patients like Tom.

Dr. Ann McKee believes some people may be at higher risk of getting the disease than others.

While examining NFL star Aaron Hernandez’s brain she identified a genetic bio-marker she believes may have predisposed him to CTE.

A discovery that could have far-reaching implications on the football field and battlefield.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you think you will ever be your old self again?

Sgt. Tom Bates: I don’t ever see me being my old self again. I think it’s just too far gone.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So what’s your hope then?

Sgt. Tom Bates: Just to not become worse than I am now.

Since our story first aired, over 100 veterans have contacted Dr. Gandy to enroll in ongoing trials to identify whether they are living with CTE. And more than 300 have reached out to Dr. Mckee about donating their brains to research.

Read the original article

By John Prybys, LAS VEGAS REVIEW-JOURNAL (August 22, 2016) — Randy Dexter and Captain are more than just dog owner and dog. That’s obvious from the way Captain looks for Dexter whenever the Army veteran leaves the room, and the way the Lab mix’s demeanor slips instantly from playful to dead serious once he’s wearing the jacket that denotes his status as a service animal.

By John Prybys, LAS VEGAS REVIEW-JOURNAL (August 22, 2016) — Randy Dexter and Captain are more than just dog owner and dog. That’s obvious from the way Captain looks for Dexter whenever the Army veteran leaves the room, and the way the Lab mix’s demeanor slips instantly from playful to dead serious once he’s wearing the jacket that denotes his status as a service animal.